The Completed Conservation Work

Introduction

Various sources show that the church has been roofless for at least three hundred years. The thickness of the walls and various architectural features indicate the building would have supported a raftered roof; this would then be covered in sarcking on to which would have been added either turf or reeds. The covering would have been whatever was available locally and the whole would have blended into the landscape. Roofs of stone or slate required stronger walls to support the weight. During the middle ages only prestigious buildings, castles and the larger churches could afford to tile or slate their roofs. It is thought that a wooden cradle to hold a bell would have been situated on the west gable. lt does not appear that this gable held a stone bell structure and perhaps some of the mysterious holes in this wall enabled a rope to be pulled from the inside.

All of the building would have been plastered and lime washed using readily available local limestone.

Internally the church would not resemble that of a modern church; the walls and roof would have been plastered and lime washed, there may well have been biblical scenes painted on to the walls. The floor was beaten earth with perhaps a covering of straw matting or reeds. The church was divided into two distinct areas, the nave took up the larger portion and was the area used by the parishioners, the smaller area, the chancel was used by the clergy. The two areas were distinctly divided in this case by a 'chancel arch’. The reason for this division was to maintain a certain mystique during the celebration of mass. Further obscuring the view from the nave would be the 'rood screen', this would be made of wood and again richly decorated. The altar was placed on or near the east wall and was used by the priest during celebration of mass.

There was no seating, the congregation stood, the elderly and infirm would bring a stool; these were the days before overly long sermons, the parishioners came to take mass and the priest would make any relevant parish announcements. The congregation would enter the nave either from a door in the south wall or one opposite in the north wall. Light was provided from the lancet window in trhaps from tallow lamps on sconces on the wall. The clergy were provided with slightly more light to perform their rites or reahe west gable or ped from the bible; there were two lancet windows on the south wall near to the altar. The priest could enter or leave the chancel through a doorway in the south wall which lead to the'cell' or 'vestry'.

Kirkton Church in the Mid 19th century

It is thought that the present church dates from the late 12th or early 13th century, it was certainly there during Bishop de Bernham's re-dedication in 1243. A church at the Kirkton was mentioned in a number of charters and re confirmation of charters throughout the 12th century. Any church prior to the present building would in all likelihood have been a wooden construction therefore all above ground trace has been lost. We can safely say that the present site has been serving the spiritual needs of the community for at least a thousand years and as early churches were often located on pre- Christian sites, this could stretch back much further.

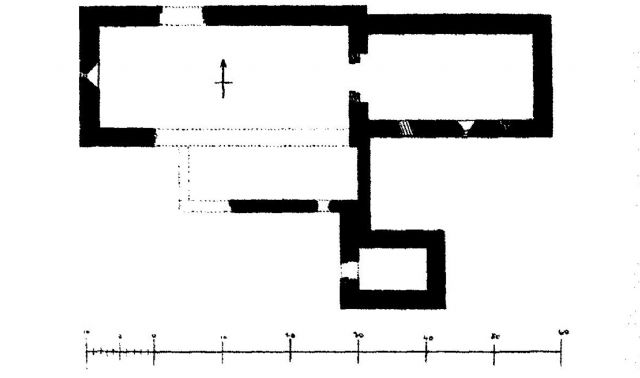

Floor Plan of Kirkton Church

This is a simple two cell church consisting of a Nave measuring 10.8metres internally and a chancel measuring 7.42metres internally.

The material used for construction was readily available locally. The distinctive light grey and orange sand stone seen throughout construction in Burntisland was available in outcrops along the edge of the Binn Hill. The most likely quarry would be that at Kilmundy which has been disused for many years. This quarry was in use long before the larger Grange quarry was exploited. Kilmundy is less than a mile from Kirkton and transportation by oxcart would have ensured a ready supply from lands belonging to the monastery at Dunfermline. We know nothing about the mason or his assistants, it can be assumed that with the building work taking place at Dunfermline labour from here may have been diverted as work was winding down. The medieval mason was not a monk but a highly skilled craftsman; the mason at the Kirkton would have combined the rolls of architect, builder, designer and engineer and would have worked on the site with perhaps a couple of apprentices and a couple of labourers. During the 12th century masonry techniques had advanced and as can be seen from the relatively uniform ashlar blocks used in the construction, produced structurally stable walls. The stone was cut using a chisel and Malott, the building was designed and erected using not much more than a set of compasses, a set-square, a staff and some rope. The pointed arch style was used in the windows as can be seen in the west gable which is complete and in the windows on the south wall of the chancel, fragments of which show the pointed apex. It is assumed that the doorways which are now gone would bear a similar style. The pointed arch is shown distinctly in the division between nave and chancel. In 2016 during conservation of the ruins, AOC Archaeology Group were contracted to create an initial measured survey and historic building record to aid conservation and consolidation work.-

Chancel Arch

The Nave

"Only the west wall of the Nave now survives It is constructed of coursed sandstone rubble bonded with lime mortar and has undergone several phases of harsh repointing, some of which appears to have exacerbated the deterioration of the stonework The gable has largely collapsed, and the wall on the west side survives to at least 13 -14 courses. Larger and more reddish sandstone blocks have been used for the construction lower down in the wall and the whole is raised slightly from the surrounding graveyard, no doubt reflecting the stone rubble tumble which may still survive beneath the ground. One interesting feature in the west elevation of the wall is three vertical stones set along the same alignment. This may reflect an infilling of larger slots in the wall (although the function is unclear as they seem too large for putlogs), but does appear to be a deliberate feature within the construction. The wall to the east side survives to at least 15-16 courses and there is evidence of some repining within the mortar joints to consolidate the wall in the past. A gravestone sits in front of the wall to the south side, belonging to Captain David Boog who died in 1807. The collapsed north and south walls of the nave have pulled away the principal surface stonework and the rubble core can be seen within on both sides. There is a central thin round-headed or pointed arched window in the centre of the wall, the exterior side with a depressed sill stone and a possibly chisel-dressed arch stone. Internally on the east side of the wall is widely splayed with the base of the opening partially broken away. However, the jamb remains and there is a single round slot towards the upper part of the north soffit. The two additional features on this wall include two putlogs running through the wall to the north and west sides of the window on the exterior west elevation on the interior east-facing wall. They largely appear as little more than holes in the wall, although to the south side of the external wall, the openings appears more prominent with a surround, lintel and sill stone. The sill stone also curiously has two circular holes within it, at present the function of which is unknown. It counterpart to the north side is merely a hole through the gaps in the surrounding coursed stonework on the internal wall, both putlogs are more regular in their shape. Very little of the north wall and the south wall of the Nave has survived. The north wall survives to at least seven courses to the west side tied into the main west wall then disappears about 2.26m moving eastwards. It cannot be seen until it reaches the Chancel wall to the east side where only a small stretch has survived and the inner rubble core is exposed. The south wall of the Nave only survives to the west end tied into the west wall of the Nave where barely two courses have survived." this text

West Gable of Nave showing putlog holes

The Chancel (Exterior)

"The Chancel survives a lot more intact than the Nave due to its re-use in the 18th and 19th centuries as a burial aisle. Externally, it has a Chancel wall to the west, a plain north wall, an east gable wall and a south wall. The Chancel wall survives to at least 13 courses and is constructed of coursed sandstone rubble. There is a small putlog to the lower south side of the wall. The original chancel arch was ca. 2.41m in width and ca. 3.42m in height (from the present ground level) and was a large pointed arched opening with simple plain voussoirs stones, although at least one has a small curved recess within, which may indicate that there was a pattern inscribed on the voussoirs; earlier 11th and 12th century churches usually had a chevron pattern of the Romanesque style. The impost to the north side has not survived well and is very weathered; the south side moulded impost has survived better. The Chancel arch was then blocked, probably when the Ayton's took over the chancel for a burial aisle, where more security may have been needed. The stone rubble blocking created a doorway with a neat chamfered lintel and ashlar above in the arch space. There is a plaque on the arched blocked, framed and supported by small plain corbels, with an inscription within reading 'BURYING GROUND OF AYTON OF GRANGE'

The north elevation of the Chancel is fairly plain, surviving to at least eight courses in a neatly coursed sandstone rubble with a central structural crack. There is a gravestone directory in front of the wall belonging to William Jenkin (71865) and Jane Jenkin (his daughter), who died in 1865. As with the gravestone in front of the east side of the west wall of the Nave, it has a tree behind it crammed up against the wall. The wall is set back slightly from the Chancel wall to the west with a small area of blocking in the junction between the walls. This may suggest a rebuild at some point of the original Chancel.

The east gable of the Chancel is equally sparse of features. As with elsewhere, the stonework is coursed stone rubble in a grey and reddish sandstone and the weathering is pock-marked on this side, and at least two areas to base of the wall to the north side have fallen out. There are no discernible features, although ivy dominates the upper part of the gable.

The south elevation of the Chancel is heavily covered in ivy. Once the ivy is removed, the features along this wall will become clearer. These include a doorway to the west side, and two windows and These survive best to the interior. The south aisle (a burial aisle) abuts this side of the church to the west side.".

The Chancel From The Nave

"The Chancel interior was converted for use as a burial aisle by the Ayton family in the late 18th / early 19th century. It comprises a single space with the chancel arch to the west wall, a plain north and east gable, and a south wall identifying the early openings, including a door to the west side and two windows and. The west wall Chancel Arch has the same style voussoirs to the interior side, with imposts in much better condition than to the exterior, although they are not identical. The stone blocking is also much cruder on the internal side. To the south of the arch is an area of disturbed stonework, which looks to consist of a blocked recess, possibly an aumbrey. The soffit of the doorway has been heavily re-mortared in what appears to be a smooth cement on the north side. On the south side, there is a square slot for a bolt; it is very likely that there was some kind of gate or bolt preventing access to the aisle, as was common in these cases for privacy and security. The north wall, as with the exterior, shows no obvious features apart from the structural crack to the centre. The same can be said of the east gable, although more may be revealed here once the ivy has been removed.

The south wall identifies the early features along this wall, including a door to the west side, and two windows to the centre and to the east. Doorway is splayed with a large lintel stone to the internal side which has remains of render within as well as some modern graffiti. It has been crudely blocked to the base with large rubble stones set slightly back from the splay. Above this, a grave marker has been placed to the exterior side; the south burial aisle is located on the other side of this wall. Window to the centre of the south wall is widely splayed with a depressed/weathered sill stone can be seen. The sill forms a ledge to the interior which seems to have undergone some modification/building up. Window to the east side has been completely blocked to the interior, flush to the wall with stone rubble. More will be revealed once the ivy has been taken down to the exterior side, although this window looks to have been set higher than the adjacent window, although this may confirm that window was modified, perhaps lowered at some point. The east wall is also fairly plain (as with the exterior) and is still heavily covered in ivy to the upper part of the gable.

There are two main grave markers within the Chancel interior, both in pink polished granite, features and. The main floor grave marker is located roughly to the centre of the room, the other a tall upstanding monument with large base and a cross set close to the east gable. The grave slab belongs to 'Roger Sinclair Aytoun' (died 1904), and the cross is his mother, Margaret Anne (Somerville 2001).

Interior of Chancel (Burial ground of Aytoun Family)

The Cell

This building poses a bit of a conundrum; the physical evidence suggests that the cell was built in the same massive early stone blocks as the church, but its date and use remain uncertain. The curved vaulted stones of the cell had to be taken down when the ivy was stripped and they were re-built with steel supports inside

Many locals recall the building with the vaulted ceiling intact. During conservation work Fife Council archaeologist, Douglas Speirs, examined the building and thought that it was contemporary with the rest of the church. The work inside the cell has revealed the top of a vault below the South doorway, which could be a burial crypt. Further work will be required to confirm this. The cell bears a strong resemblance to the one on Inch Colm which pre-dates the Abbey by many centuries.

The Cell showing stainless steel braces

"The Cell (as it is most commonly known today) is set apart from the main kirk and consists of a small room, ca. 3.71m x 1.92m (internally) and possibly served as an original Vestry; it is annotated as such on 19th century plans. Little could be viewed of the surviving walls of this structure due to the extensive ivy growth, although a small exposed area to the south elevation shows it to be the similar coursed sandstone rubblework seen to the main lark There are a number of interesting features along the west wall, including a blocked doorway and another crudely smaller stone-blocked opening to its north, possibly a recess. Set above this are two stones which show signs of potentially historic graffiti, including a stone with the initials 'WR 'and another with the figure '800The historic 1880s photograph shows that there was a chimney flue to the east side of the south elevation of the Cell, and although this has gone today, there is a small depression / gap in the stonework here today, which may shed more light the exact character of this feature. The 1884plans of the kirk also show a doorway to the east wall. Whilst there appears a slight depression in the stonework here, more will be ascertained after the removal of the ivy. Another interesting feature associated with the Cell, and indeed perhaps the kirk, is a fragment of pointed arched stonework lying on the ground to the southwest of the Cell. ".

South Aisle

"Very little of the South Aisle now remains. Access to the Cell from the South Aisle was to the west side of the north wall of the Cell The west wall from the Cell thus continued northwards to then turn 90° to the west to form the south wall of the Aisle. It appears that more security was added to the adjacent burial aisle in the form of railings, one of which has been placed on a former sill for a window. To the east side, the east wall abuts the south Chancel wall. It is a heavily rendered wall, so it is not clear whether this belongs to the original Aisle or is a later wall built to accommodate the adjacent burial aisle to the east. On the west side, the rubble core is exposed where the north wall of the Aisle has collapsed.".

The Cell and Remnants of the South Aisle

The Boundary Wall

It is unlikely that the present boundary wall was in place at the time the kirk was abandoned, it would however have followed not long after. The wall is constructed using sandstone from the same source as that used on the church. In all probability the rubble from the church would have been used to repair the wall over time. The gate piers have been described as typically 18th century. The only early evidence to a boundary wall is Roy's map of the 1740s showing an enclosed area.

Boundary wall